Survivorman

or feelings of ineptitude: part one

Picture me, seven years old, accompanying my father to the local bookstore. I am wandering the children’s section when I come across a small manual of sorts, an illustrated survival guide for kids. I thumb through the pages and am overcome with urgency to study its content: how to light a fire in the woods, how to treat snake wounds in the desert, how to fashion a makeshift water filter, etc. Not only does the book catalog all of the very plausible, life-threatening situations a child in the city will most definitely come across in the future, it guarantees my survival in the opening pages:

“Follow these instructions, and you will be sure to survive.”

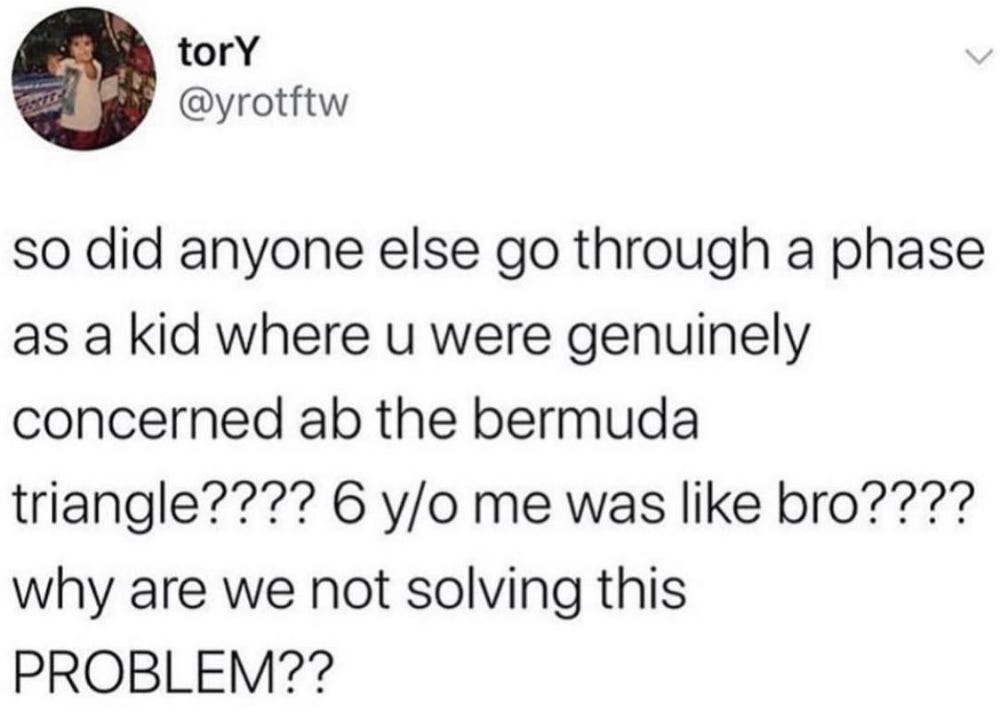

The next couple of months are mired in hypotheticals: what if my plane were to crash in the middle of the ocean? What if my leg were to break at the top of a mountain rage? Danger — and not the insipid, hit-by-a-car or get-abducted-by-a-stranger kind of danger, but the more exciting variety found in cautionary tales of adventurers — lurks everywhere, or at least within the imagined tragedies that I’m certain will befall my life, like mishaps on Mount Everest or a visit to the Bermuda Triangle. Every night in bed, I replay in my mind the steps to making a fire with two pieces of wood, because surely, this knowledge is bound to come in handy at least once in my lifetime. I fall asleep with the book in hand.

One Sunday after church, I tell my two younger cousins we should start a fire. We’re playacting a survival scenario on the playground, where the merry-go-round is the deserted island, the surrounding sand the ocean, and our only tools at hand are the couple of branches found under nearby bushes. I instruct them to rub the two sticks together, and they humor me at my insistence that we’ll see them spontaneously combust. Minutes pass with no sign of fire. The wait is agonizing, as is the slight to my pride. I take over, intent on seeing a strand of smoke, grinding them until my arms are numb from pain. Eventually, my cousins lose interest and leave me be, alone on the island, sheepishly twiddling the unburnt sticks.

Days, months, years pass without the slightest danger. Life, for better or worse, turns out more convenient and harmless than I imagined, and I soon move on to another obsession. The manual is lost between moves.

Years later, I’m watching Cast Away with my mom. Tom Hanks is using two pieces of wood to light a fire, and I’m taken back to my childhood. The movie is as exciting as the scenarios I weaved in my daydreams, albeit much longer. Mine involved a day, maybe a week tops, of being stranded; Tom’s been on the island for years and is talking to a volleyball. Such is the price of survival, I think. The emotional turbulence of a man learning to fend for himself using nothing but sticks and stones and an assortment of undelivered FedEx packages — it’s quality entertainment.

On another night, Discovery Channel is hosting a Man vs. Wild marathon. The host’s name is Bear and, with an ear-to-ear grin, he’s gutting a camel carcass, explaining that sleeping inside it will offer the best protection from a sandstorm. I’m entranced. He retches and holds his breath, elbow deep in rotting intestines to carve out the remaining bits clinging to the ribs. At one point, he’s wrestling the disemboweled body by the legs to flip it over and finish skinning the hide to use as a blanket. The end of the segment features Bear slithering inside the camel and yelling from the depths of the animal, “…and I’ll be 100% protected from the sun!”

I watch a few more episodes just to see him flex his iron stomach, drinking the blood of a caribou straight from the jugular, like taking a sip from a water fountain, or munching on handful of deer shit he gingerly picks from the ground. The physical endurance of a man demonstrating the most outlandish of diets — it’s quality entertainment.

I ask myself if I’d ever be able to eat deer shit for survival. I’m sure I could, but then again, I wonder if I’d ever even find myself in such a situation. The answer, of course, is unlikely, but how unlikely is it exactly?

I take a mental note: dead camels save lives in the desert.

Years later, I’m wandering around a quiet town called Badami in Katarnaka, India, a temporary stop on my journey southbound to Bangalore. En route to visiting cave temples, walking through pastel buildings on dirt roads, I stumble on a cobble-stoned path that extends away from the town and far into the barren landscape. There doesn’t seem to be an end, or at least one I can see, and I’m curious where it leads. I start walking.

An hour passes, and I’m already out of water. The path isn’t lined with any trees or structures to provide relief from the midday sun. Not a soul has crossed my way, and I mull over the same question I’ve had since my first step: where is this taking me? A follow-up: who is this for? Presumably, it’s connecting one remote town to the next, but there’s no indication of that being the case — no signs, no direction but forward. For all I know, it could be an abandoned road that leads to nowhere, a story with no conclusion, and the sensible part of me begins to nag that it’s time to turn around.

I spot a snake a few feet ahead. It’s black, and I see the faintest glimmer against its scales as it moves between pieces of rubble next to the path. I freeze, and ever so carefully backpedal until I’m certain it’s not in range of my bare ankles. Do I know what a venomous snake looks like? Should I even be taking the chance? No water, a few rupees stuffed in my pocket — I feel naked against danger. The story is now crumbling into something more reckless than I intended. The choice is clear: I turn around and saunter back to where I began, parched and unsatisfied, but safe.

Lying on my motel bed with two liter bottles of water, I nurse my sunburns, wondering what lies at the end of the path.

July 2020: I’m camping with friends on top of a mountain in Catskills, NY. We are attempting to make a fire with newspaper scraps brought from home, plus kindling we picked around the campsite. In preparation for this moment, I’ve watched a couple of YouTube tutorials on how to start a campfire (even in the rain), which make the task look easy: build a structure for optimal airflow and fan from the bottom to allow the flames to rise. Generally speaking, I can follow visual directions to a tee, and having been in the presence of former Eagle Scouts and friends who played with fires as kids, I feel sufficiently ready before the hike.

Reality is not so kind. The sun begins to set, which brings forth less a picturesque vista but a timer for when the lack of fire becomes more than just a small nuisance. Even with a lighter, the wood refuses to catch, and I’m exasperated at both the impotent smoke and my lack of competence. I’m not particularly convinced by antiquated answers for what makes a man, but out in nature, when I’m tired and cold and lacking a roof over my head, I want to believe that I can be as capable as my primitive forefathers, a master survivalist, someone who can control the heat, tame the fire, start it and grow it on command. It doesn’t seem an exaggeration to say my masculinity hinges on it.

The fire eventually comes to life. We sit around to make s’mores.

At lunch, my coworkers tell me about the show Survivorman after lambasting Man vs. Wild as fake and performative. If there’s a camera crew that follows the host everywhere, where are they staying and what are they eating? Are we really to believe they’re cozying up in sleeping bags and looking the other way as Bear sleeps inside a dead camel? Something doesn’t add up.

The Internet tells me Les Stroud is the real deal. The premise is largely the same as Man vs. Wild — a man is dropped off in some distant wild and documents his survival — except Les is by himself with a camera and films his own expedition. It’s somewhat like a travel show, like Parts Unknown, but while Anthony Bourdain was eating his way to bridging cultural divides and persuading the audience of a welcoming world, Les is surviving his way to showcasing the invariably hostile corners of the planet. The pilot episode lands him in Boreal Forest, Northern Ontario, where he simulates becoming stranded after a canoeing accident — no food or shelter, only a single match in his possession.

“Every year, nearly two-thousand people are lost out here,” he says after listing out the possible dangers he’ll face: cold, exposure, starvation, predators.

After a few episodes, I understand why he’s so idolized by outdoorsy communities on the Internet. There’s something oddly calming about his personality on screen — odd because he’s remarkably levelheaded throughout his escapade, even when it’s Day 5 and he’s resorted to sautéing water lily tubers. He’s also a knowledgeable practitioner, thoroughly explaining his thought process while foraging for supplies, building shelter, starting a fire, etc, enough that, even if you’ve never stepped foot in a forest, the show would’ve prepared you with some basic instinct around how to extend your life in dire scenarios. This level of competence, I think, is what makes him so fabled.

I realize the entire series is available on YouTube, and it’s suddenly two o’clock in the morning. What is it about survivalism that engrosses us? A part of it must be our morbid fascination with the fringe of human nature, a break from tedium, and in light of that, the instant gratitude we feel for the overlooked conveniences of our own lives. I’m reminded of the scene in Cast Away when Tom is alone at his post-rescue dinner party, quietly scanning the amenities laid out on the table, including a lighter. It’s unclear if what he’s feeling in this moment of clarity is dejection, admiration, or both:

Or maybe it’s the opposite. I read an interview with Les, where he supposes the larger question that draws an audience to his show is simply, “Can I do that?”: could they leave everything and all behind and journey out into the wild? Would they survive, or would they flail? The pull, then, isn’t simply about checking out the tribulations of a master adventurer, but rather in witnessing it, re-imagining oneself as something similar — bold enough to dare to venture, capable enough to handle setbacks. It forces us to reconsider life’s security less as a gift than a curse of complacency, and in recognizing this, allows us to dream of something exciting, dangerous, a masochistic fantasy to test our mettle.

I put on another episode. This time, Les is in the jungle of Papua New Guinea, sick with diarrhea, vomiting, fretting over a developing foot fungus. He narrates:

Existence in the jungle is a dark closed-in experience that can play on the psyche in horrible ways. Nightmares are dogging me constantly in here. Often I dream of being somewhere else, some place pleasant. But when I wake up, my heart drops as I realize I’m still in the jungle.

I look back on my own small adventures and near-mishaps and the calculated recklessness with which I’ve lived, and I wonder, can I push it further? Should I push it further?