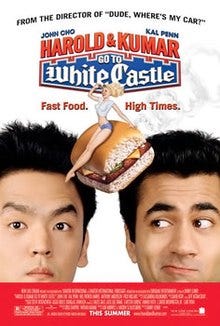

Everything you need to know about the film is in the title: two men — one docile by virtue of his name, reminiscent of fatherhood or suburbia, the other of a clear “foreign” descent, atypical of protagonists in Hollywood comedies at that time and prior — embarking on a journey to feast at the fast food joint White Castle, a most American of institutions. Presumably, they are stoned or drunk or both, for there aren’t too many circumstances that elect White Castle as the destination itself and not a detour from the main quest. But the two protagonists are seeking it out, explicitly going to it, which, given that they are high, seems a significant showcase of willpower and misplaced priorities. Minority heroes, subverting Asian stereotypes, hints of drug use, a yearning for adventure and, perhaps, a pursuit of the American Dream itself — it’s all right there in the title.

2004 is often touted by the popular mass as a notable year for comedies: you can find anything from the millennial favorites (Anchorman, Dodgeball) and satires (White Chicks), to “sex comedies” (EuroTrip) and coming-of-age films (Mean Girls, 13 Going on 30). The list goes on: Napoleon Dynamite, Along Came Polly. It’s less that they are timeless — the more crude humor have certainly lost its luster with time — but rather that they all embody the same type of inane, happy-go-lucky sensibility as laugh tracks in prime time sitcoms. The general vibe of these comedies can be best described as “untroubled” — lighthearted, often formulaic, devoid of anything particularly illuminating about the seriousness of life. And that’s the point: you watch it explicitly not to think. And if you don’t think too hard, it all feels good and harmless, which is exactly what most millennials are reminded of when they scroll past these titles on Netflix and are brushed with pangs of nostalgia.

Interestingly enough, something else these films all share is the sheer whiteness of the cast (not including, of course, White Chicks and Soul Plane and other movies catering to Black American audience), which is still in congruence with how untroubled they all seem. These movies signify the tail end of an era when the white American populace could live carefree and careless lives on screen, because they were the whole of America and not just an aspect of it. You’d be lucky to see an Asian character with a speaking role in any Hollywood films then, and if you did, you’d probably find them pigeonholed into a karate-chopping, keyboard-clacking corner, and if not, they’d probably be lingering in the background with one-line quips. Prior to H&K, John Cho (Harold) was mainly known for his role as the “MILF guy” from American Pie, and while that’s not nothing — at the very least, we could say an Asian man helped coin the truly timeless term and all its progeny in the modern vernacular — it’s not quite the something that we were willing to settle for. Kal Penn (Kumar) was of similar stature, though he played a more prominent role in another 2000s comedy Van Wilder as a sexually repressed, heavily accented exchange student from India. Penn was born in New Jersey. But on screen, he was a caricature of a foreigner, whose ultimate salvation came at the hands of Ryan Reynolds helping him indulge in American debauchery by sleeping with an American woman. He was a cinematic prop, painted a shade of brown deemed permissible for public consumption. This, too, couldn’t be the something we should settle for.

When I was twelve, I wasn’t entirely cognizant nor critical of the representation problem that I am writing about in retrospect. I just watched what was available, which, at a remote boarding school in the mountains of New Hampshire, was limited to the secret stash of DVDs a floormate kept tucked in his closet. Sunday afternoons were spent huddled around a laptop. R-rated (or better yet, “unrated”) comedies were the top choice, and understandably so: we were puberty-stricken boys living in the wilderness, fiends for a half-second glimpse of a boob. Crude jokes were plentiful, a few of which propped up the Oriental as a figurehead for whatever suited the punchline — indistinguishable, hypersexual, silent and foreign. I wasn’t particularly offended when I came across them, especially when, at times, my white friends would glance at me while laughing, as if seeking approval, hoping that seeing me laugh along would erase any unspoken boundary the joke may have crossed. Frankly, I didn’t know what to be offended at. Being a transplant to the US and not a native granted me the privilege of seeing my people thriving on screen elsewhere in the world; these satires, if you could call them that, were specific to this world I was merely visiting at the time and did not weigh as heavily on my identity, or at least not then.

Even so, I wasn’t too ignorant of the fact that I had not watched a single person who looked like me get into the sort of shenanigans all those white folks did on screen. They were going on spontaneous road trips, losing their cars, chased by angry mobs in a wholesome sort of way. All things considered, maybe that wasn’t such a terrible thing, to be a constant voyeur in a white man’s world, to know that this life of heedless idiocy wasn’t for me or my people. But for all the trouble they got into, throughout all those whacky misadventures, they seemed to be having fun. And I, too, wanted in on the fun.

One Sunday afternoon, we watched H&K. It wasn’t that its humor was groundbreaking or any less crude than other films in the similar stoner-frat-bro comedy genre. Many of the jokes on sex and race went over my head during the first screening, and I also watched it without the slightest inkling of what weed was (the entire premise of Kumar’s dream sequence when he fucks an the oversized bag of weed did not dawn on me until years later). But even if I could only enjoy the basest toilet humor, I was entranced, because, at the heart of it, the overall narrative arc was so familiar, so recognizable, and it was being carved by two Asian heathens, one of whom looked like me, talked like me, suffered from similar pangs of diffidence. They were on a zany adventure with lots of sex, drugs, a cheetah and Neil Patrick Harris. They stole a car and went hang gliding to eat burgers. They spoke of the demons haunting first generation kids. Even to my middle-school self, this felt special.

I watched it a second time in high school. I had by then reckoned with the hardships of being a minority a few times over, though short of the wisdom needed to fight the swell of insecurity. Being called a “chink” hits different when you are fourteen, when each slur tugs at that delicate thread of your identity and forces you to wonder why you seem a source of amusement to so many strangers. The film, in that sense, was a saving grace. I felt an intense pleasure seeing the heroes walk away with victories against bigoted cops and “extreme assholes”. Watching a Korean-American man show a glimmer of cool and confidence and tell his white co-workers to fuck off was indelibly satisfying. And how sweet was the scene of Kumar yelling, “Thank you, come again!” as the duo drives away in the stolen vehicle, middle finger out the window? These scenes were cathartic, a chef’s kiss.

Granted, no race was safe from the film’s vulgarity, including Asians, as the writers seemed to intentionally satirize as many demographics as possible. It’s a common trope in satires, believing that they can’t offend anyone if they offend everyone. But the difference between H&K and something like Team America (which, by today’s standards, is so outlandishly offensive it’d never even be considered for green light) is that the story itself centers around the redemption of the very characters who would typically be employed as crutches for a white narrative. Take, for example, the most derivative part of Harold’s character arc: in the beginning, he’s too awkward, too socially inept, a real travesty of a Man, who would rather crash his car down a hill than say hi to his neighbor Maria. But by the end of the film, he approaches her, modestly confident, transformed, and professes his feelings.

Indeed, he gets the girl. Was it a cliche? Perhaps. But I can’t understate the validation I felt seeing, for the first time, a man of my color being desired in a Hollywood movie. The Asian Man in Hollywood can often be described as the antithesis of charisma: inarticulate, dull, carrying a great capacity for impotent sympathy. Such a persona can inadvertently bleed into the public psyche as a truth, yet we are not provided any evidence in mass media to believe the contrary. Harold’s character development, as trite as it may feel, offered us exactly that: that an Asian man can be a source of longing and romance, and that he, too, can exemplify the kind of poise placed on the altars of the Hollywood Man.

That was what made H&K special for me. It was a subversion of the status quo of the Asian-American portrayal, which brims with marked complicity — tiptoeing around racists, avoiding confrontations, passively allowing others to take the foreground while we drift towards the back. It proposed an alternative: that Asians-Americans are, in fact, Americans, and, by the virtue of that label, should be granted the same rights to self-actualization and manifest destiny as our paler compatriots on screen. Isn’t that what representation is all about? To not just wait and be placed, but actually place ourselves in the foreground? Harold puts it succinctly, staring longingly across the parking lot at Rosenberg and Goldstein inside Hotdog Heaven Chili Dog:

I want that feeling. The feeling that comes over a man when he gets exactly what he desires. I need that.

This is just the heart of the American mythology, retold for us minority folks. Watching the movie, I wanted that for Harold and Kumar, and I wanted it for John Cho and Kal Penn, and I wanted it for myself too.

Whenever I try and justify this movie being in my personal top-ten list, I have to remind myself the context. What I remember about it and what I love about it doesn’t negate its problems. A decade later, I still laugh, but not as much, and not for the same reasons. I often find myself chuckling not because I find the jokes funny, but because it’s absurd to me that an audience, myself included, used to laugh at them without a second thought. In reverse, progress can be comical.

I also cringe a few times at the overly crass bits (e.g. British twins on the toilet), though what specifically casts a doubt over my fondness of the film is the self-racism perpetuated by Harold. The portrayals of Maria as the prize and Cindy Kim as a participation trophy only reinforce a false totem pole of race and desirability. He also avoids going to the East Asian club at Princeton and frets over being called a “Twinkie” (yellow on the outside, white on the inside). He seems to covet this separation between himself and his community for reasons that aren’t articulated, though one can guess he’s internalized the stereotypes and thinks he’s above those who choose to wear their culture proudly. The ending never resolves this tension, and Harold, though more self-assured, doesn’t embrace his heritage any more than in the beginning. Yes, we do see that, in another twist, the East Asian club turns out to be not just a group of stereotypical bookworms, but hardcore partiers who can throw down. But surely we’ve progressed enough in the last decade that we won’t need another movie that plays into the stereotypes, just to make the point that, no, Asians can in fact be cool.

There’s a part of me that can still enjoy the antiquated humor, but only from a distance. I don’t think I’ll watch it again sober, and you could argue it was never meant be viewed without a joint in hand. But even dumbed down in a haze, I can appreciate how extraordinary it is to watch, ten minutes in, a couple of Asian guys unwinding after work, smoking pot, watching TV, like normal twenty-somethings in America. They aren’t punching or kicking or hacking and crunching numbers. They’re just getting high.

Incremental progress.