An embarrassing story

Geishas in New Hampshire

A few weeks ago, I was out with some co-workers when they asked me what my most embarrassing story is. I thought about divulging myself more than usual, seeing how I prefer to keep my guard up at most corporate outings. I’d rather listen, especially if we’re at the point in the night when everyone’s a few drinks deep and softly prying for dirt. Dave passed out on a porch in Brooklyn, Karen made out with her boss at the offsite, etc, etc. Shame is a devilish feeling. I, too, have been frequently steeped in the flush of the moment, that universal suffering of being too aware of yourself, when you turn inwards and die by a thousand stares. I figured I could better write the story than tell it.

I was in seventh grade at a boarding middle school, tucked away in a remote corner of New Hampshire. There were mountains, a lake, big grassy fields powdered with snow in the winter. Picturesque New England. About a third of the student body were there as a pricey form of punishment by parents hoping that a stringent environment — dress codes, weekly sermons at the chapel — would bend the arc of their child towards something more presentable. Another third were kids, mostly international, looking to get into a reputable high school. The last third were there to play hockey, which was what the school was known for around the region. It was also all-boys. Hormones ran high and fights were customary, though kept on the hush lest we were caught by a teacher and expelled.

I didn’t expect so much angst when I first drove into that wooded campus. I was just a kid, naive about the cruel kinks of growing up. Universally, middle school seems to be the inflection point when many unleash their inner asshole, and there was a handful here too, especially the white kids who’d never stepped across state line. They’d say ching chong and stretch the corners of their eyes, and I’d stew quietly, groping in the dark for words that’d hurt the same and failing. The inadequacy was wildly infuriating. What could you say to a blue-eyed boy with a good family and private school education? Not much, I found.

In the Fall, my English teacher Mrs. Mendelsohn stopped me on my way to assembly to ask if I could audition for the Fall play. She was the theater director, and I was actively avoiding a run-in with her outside the classroom. I’d heard a rumor from other Asian classmates that she was on the hunt for a boy to play a part in her production, a certain role that would be rather unbecoming. I froze, of course. Saying no wasn’t yet a muscle I had trained. She was also my teacher, an old white woman imbued with that aged blend of sweet and frightening, who seemed to wield more power over my worth as a student than probably true. 3 pm at the auditorium, she said. I obliged.

There, she handed me a script. The title read The Teahouse of the August Moon, and highlighted was the name “Lotus Blossom”. She went on to tell me that I would be auditioning for the role of a geisha in post-WWII Okinawa. I blinked twice. What’s a geisha, I asked. She didn’t need to explain its complicated cultural significance and history, for it was enough to be told the role was for a girl to send me spiraling. Female impersonation? My twelve-year old mind could not fathom the injustice of my predicament. Lotus Blossom is the quiet star of the play, Mrs. Mendelsohn reassured, as if I should cherish this opportunity she had bestowed on me. I thumbed through the pages and saw that my lines were in Japanese, phonetically written out in English. When my time came, I hopped on stage and read aloud sounds I didn’t know the meaning of. She clapped. I sighed. No one else auditioned.

I don’t recall much of the plot, which had some subtext around overcoming cultural differences. I remember in one scene I needed to take an officer’s shoes off while he tried to get away, a playful charade between those caught on opposite sides of the language barrier. There was also a solo dance sequence. It was for the opening night of the titular Teahouse in the second act, and as the Geisha of the town, Lotus Blossom is instructed to perform a graceful choreography for the Americans, a ceremonial gift. Every week up until opening night, I went to practice a watered-down imitation of a routine not unlike in Memoirs of a Geisha, where Zhang Ziyi sensually bounds and twirls on stage with a fan in each hand:

Did I feel like Zhang Ziyi? Did I want to feel like Zhang Ziyi? I’ve never seen the film, but I read that it’s not very accurate. No matter, for this was a middle school production in the rural Northeast, and cultural sensitivity was not a priority. We were going for a vibe here, one that exuded oriental grace, a coy, suggestive kind of passivity. I hated it, less because I had the sensibility to recognize what was tasteless about this portrayal, more because I was going to dress up as a girl. A boy playing a girl wasn’t uncommon given that this was a single-sex school. I was told, perhaps to soothe my worries, that every season, Mrs. Mendelsohn would coax some unwitting group of students to overlook their juvenile insecurities and put on a wig for the school play. It was also theater, and men had dawned dresses on stage to oppress women since the ancient Greeks.

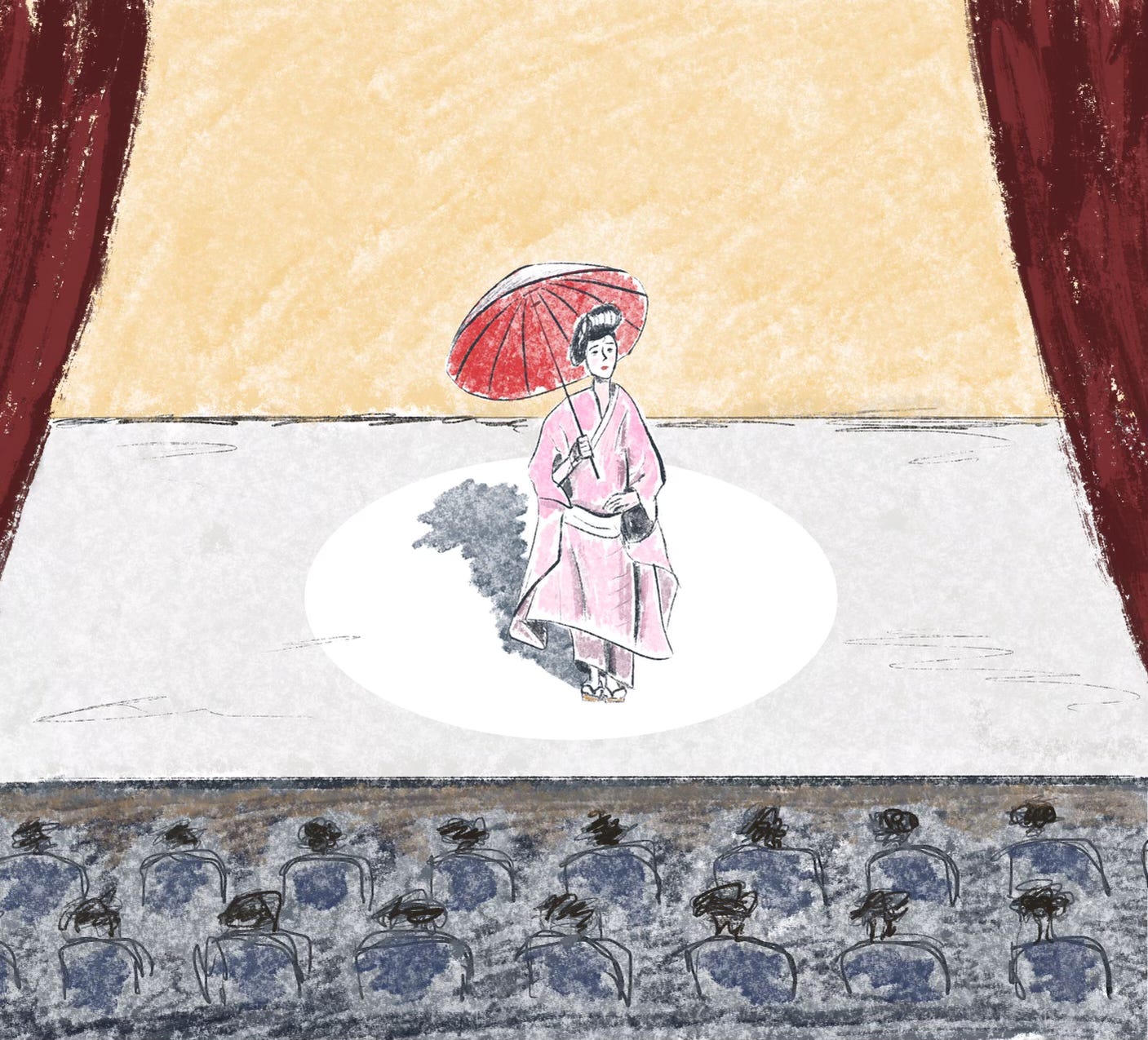

This didn’t lessen the blow for me. Word got around campus that I was playing a prostitute. Heckling was expected, but I knew I was finished when even the kids at the bottom of the food chain were snickering behind my back. Masculinity was a fragile currency then, and you could be bankrupt at any moment. We tackled each other in the hallways, gave each other charley horse and bruised knuckles, punched each other in the nuts and called them gay if they squealed. If you were bad at sports, you were gay. If your voice cracked, you were gay. And as long as someone else was gay, you were not, and it was on this non-gay side of the line that folks could find some semblance of social security. Being a boy dictates there is no avenue to empathize with others except through violence; only by tearing another down can you scrape together some pretense of an emotional connection. And here I was, offering myself as the sacrificial lamb for the collective to deflect all their innermost gayness towards, a cross-dressing caricature. Each day before opening night, I would dreadfully imagine myself on center stage, wounded by the gaze of my peers. Dancing, twirling.

I swear I blacked out on stage. I remember the clacking of my loose geta. My itchy wig. How hot the light felt on my face, plastered in white. The nameless smirks I could faintly make out on the other side of that light, their muffled laughter. My heartbeat. I could hear my heartbeat louder than the song of my dance, as I imagined my peers all squirming with ill-spirited joy in the dark. I didn’t crack though. I finished my scenes, bowed, then skirted offstage, where Mrs. Mendelsohn gave me a hug and said I did beautifully.

After the show, they fed us coke and pizza, and I walked back to my dorm alone. I’m too far removed now to remember how I truly felt, but I’d imagine it was pain. Maybe a tinge of pride, but mostly pain. And I probably plotted a plan for redemption that never came to fruition, somewhere out on the football field during practice or in the dorm rooms, tangled in a fist fight to clear my name. I can see now that I was deathly insecure, delicate in every way except my body, which I was so eager to hurl at another to hurt, to bruise, in a way to express what I couldn’t with my words. Ultimately, I could’ve just said no at the beginning. Maybe this is why I’ve long consider this an embarrassing story, because of how little agency I thought I had. It would’ve been one thing had I done this out of self-respect, or a quest for it, like a story of redemption, of overcoming fear and becoming whole. But I only did this, truly, to appease an old lady and aid in her pursuit of the arts, antiquated and all. I didn’t even have any theatrical ambitions. This wasn’t fucking Glee. I was just a kid who happened to be Asian and available, and on the other side of that grey acquiescence was not some bold epiphanies, but only fear and shame and sweet relief that I could step back into the shadows.

I suppose what I long for now for my twelve year old self is a type of willful isolation. I wish I had the space to say no, to say yes, to feel the lightness of a thousand stares and remain unbothered. To carve an identity free from the whims of others. That sounds either too fantastical or hermitic, I admit. Life rarely affords one to be so carefree, and we are all performing a charade for the approval of the masses to some degree. I just wish I wasn’t so ill-prepared to step into the spotlight, baring my insecurities and all, for a role so challenging, for an audience so ungiving.

The worst bit: it was a two night production, the second of which was for the parents. I chose not to invite my mom, as it would have been a losing battle to try and explain to my conservative mother why she was paying an exorbitant tuition only to see me dressed in a pink kimono. The afternoon of the second show, I felt my stomach rumbling. By that evening, I was deathly ill with a stomach bug, pale even without the makeup, rushing in and out of the toilet in between my scenes. At the end of Act I, just as my co-star uttered his last words and the lights dimmed, I emptied the contents of my stomach on stage. Chunks splashed onto my kimono. I stumbled to the bathroom, lit only by the red glow of the exit sign, and saw myself in the mirror: cold sweats, bloodshot eyes, wig disheveled, vomit dribbling down the corner of my lips. I didn’t recognize myself. A fever dream.

Alas, the show must go on. We waited until the stage crew mopped up my insides, and I danced my dance for all the adults in the room. Maybe they thought I was brave, or maybe they felt bad. I was probably all of that and more — brave, naive, confused.

Just a boy in search of validation.